There are literally millions of books giving advice on how to build effective and high-performance teams. Some were written by theorists who have never experienced the advice they give. Others were written by highly intelligent managers with great business successes. Daniel Goleman, the bestselling author of *Emotional Intelligence*, wrote about many of them: CEOs are hired for their intellect and business expertise and fired for lack of emotional intelligence. There are also many books written by outstanding and successful sports coaches about the best way to perform. So why bother to write yet another article on team performance and building? The answer is quite simple: Because our 5-step cycle works, is effective and available to everyone through our Mission Team workshop!

Our approach is not based on some kind of academic theory. It has been drawn from observing successful performance-oriented individuals and teams in business, sports, and arts worldwide. These observations were then reconciled with constantly updated findings from psychology and neuroscience and transferred into an easy-to-understand and use model. The model has then been applied, adjusted according to the gained experiences and new insights, and adapted again and again.

Over time, these insights and observations have led to the development of products that help others enhance both their personal growth and collaboration within teams of various types and sizes. These include in particular Mission Team as well as the educational products mission future and mission future Team, along with the career counselling product Mission Career. All these products cover either the entire or parts of the 5-step cycle and can be seamlessly integrated into it.

The five steps that lead to great team performances are represented as a cycle. From the team’s point of view, performing at the top level is not a one-off but rather a never-ending, permanent process. No two people perform the same every day. There are always ups and downs. In the real world, teams not only have to deal with themselves but also with external influences that are often beyond their control. The truly outstanding teams are characterised by the fact that they always adapt, constantly bring energy into the team, and never stop taking the same five steps, a little differently every day, but always with a goal-

oriented, constructive, and open attitude. In other words, this cycle does not only concern managers, coaches, or team leaders. If a team wants 1+1+1+1+1+1 to equal 8 (and not just 6), this is only possible if every team member is able and willing to contribute to the team performance every day, again and again.

However, even if the steps are organised as a cycle, they build on each other. From the point of view of the individual team member, it therefore makes sense to go through the process in a certain order first, to then supplement, change, or repeat it if necessary.

I personally can’t entirely separate the chronological order of the first two steps in our cycle. In my case, gaining self-knowledge was closely intertwined with recognizing the value of diverse perspectives and approaches. Please bear with me as I provide some context; it will deepen and nuance the insights that follow.

Improving my self-knowledge and recognizing diversity: An introduction

More than 100 million people watched the TED Talks of Sir Ken Robinson, undoubtedly one of the most eminent experts on education and learning of the last thirty years. In his 2010 TED Talk ‘Bring on the Learning Revolution!’ He explained concisely why self-knowledge, especially of your talents and strengths, is so important: I believe fundamentally… that we make very poor use of our talents. Very many people go through their whole lives having no real sense of what their talents may be, or if they have any to speak of… I meet all kinds of people who don’t think they’re really good at anything. I meet all kinds of people who don’t enjoy what they do. They simply go through their lives getting on with it. They get no great pleasure from what they do. They endure it rather than enjoy it and wait for the weekend. But I also meet people who love what they do and couldn’t imagine doing anything else… And it’s not true of enough people. In fact, on the contrary, I think it’s still true of a minority of people. And I think there are many possible explanations for it. And high among them is education, because education, in a way, dislocates very many people from their natural talents. And human resources are like natural resources; they’re often buried deep. You have to go looking for them, they’re not just lying around on the surface. You have to create the circumstances where they show themselves.

This last statement by Sir Robinson is the biggest difference we observed between the worlds of sports, arts – especially classical music – and labour. Looking at sports teams, chamber music groups, or orchestras, we often see up to 85% or more of the team members being aware of their talent, of their strengths, and full of motivation to use them for the success of the team. In the world of labour, we often see over 85% for whom this is not the case.

The process of perceiving, of recognising oneself, is the first step to success. Planning and acting successfully require knowledge of your strengths, knowledge of what you can be sure about yourself. Sometimes, these strengths and talents are easy to identify, and one is given plenty of opportunities to find out about them. Talents in arts and sports are often discovered and promoted at an early age. Identifying – often subconscious – strengths that allow someone to become a great professional is much more difficult. Everybody seems to speak about the importance of soft skills like collaboration, communication, or critical thinking. But often, little or no support is given in discovering and training these skills. Rather, our education and training system is focused on finding errors and eliminating weaknesses. No wonder that most people are much better at explaining what they are not good at, what they have problems with, rather than the strengths and talents they have been gifted with. It’s time for the scales to finally tip in the other direction.

We claim that improving self-knowledge is the first step to improving team performance. We have too often seen that team members cannot articulate what they can bring to the team and where their special strengths lie. To discover and promote self-knowledge, a process including the interaction between at least two involved parties is ideal: individuals and their team, their family, a coach, etc. For those who do not already have such a process in place, we have created the Visual Implicit Profiler (VIP)®, which will start you off by enabling individuals to recognise and – at a later stage – utilise their talents and strengths. If you wish to learn more about how the Visual Implicit Profiler (VIP)® works, please read our article: Visual Implicit Profiler (VIP)® and have a look at an example of the Personal Strengths Profile it generates.

People are diverse. They come from different backgrounds, have different genders, etc. Prejudice against people based on their ethnic background, religion, sexual orientation, disabilities, gender, or age still very much exists. And we certainly must do more to get rid of all kinds of misconceptions and the injustices that result from them.

However, this is not our main objective when we talk about recognising diversity and otherness. Rather, we would like to focus on an even more multifaceted aspect of human beings: their personality. Achieving great success in a team, a group, or a company requires the full potential of everyone involved. If you are precise, work methodically and strategically, you are not necessarily creative, spontaneous, and empathic at the same time. Once you start exploring, first your own and then the strengths of others, you will most likely come to the following conclusion: Some people are more talented than you in certain areas, and you are more talented than them in others. Acknowledging gender and background is great. But it takes an extra effort to find out about people’s mentalities, how they are wired, how they perceive and how they come to their conclusions. Unfortunately, we tend to form an opinion (all too) quickly.

Each of us has had first encounters that were a disaster. We may, for example, have thought that the other person was arrogant, loud, or not really likeable. A few milliseconds were all it took us to reach this verdict. People size up and form opinions of others with lightning speed. From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to do so seems quite beneficial; it allowed people to opt for flight or fight quickly. Our radar for people is located in a genetically “age-old” area of our brain.

When radars capture an object, the information they provide is imprecise at first. Only once there is visual and radio contact is it possible for people using them to identify what or who they are dealing with, and what the intent or destination of the “object” might be. Our radar for people, too, provides us with little information with respect to personalities or motivations. The power of the first impression, however, is enormous. Then, we tend to confirm those first conclusions, regardless of whether the first impression was negative or positive. And what is more, we rarely consider in what circumstances we formed that first impression. Maybe we were in a particularly bad mood – or in high spirits?

In any case, all we need to gain more insight into the attitudes and actions of others are curiosity, an open mind, and some time. Unfortunately, few people, and even fewer companies, take this time to take another look. We need sufficient background information if we are to assess the perspectives and logic of others and use them for the success of a group. Integrating these aspects allows us to create successful teams.

In the next step, we must accept the diversity and otherness we recognise. But there are a few issues with this. For one, we prefer similarity to diversity, confirmation to opposition. As soon as our brain identifies familiar patterns, it is happy. We like whatever confirms our thinking patterns and our own reasoning and tend to dismiss other information as fake news.

In his book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman describes this phenomenon as confirmation bias. This is just one of the many fallacies of the human perception and decision-making process, which were described so impressively and comprehensively by Kahneman. A lot of these fallacies are rooted in the strength of our beliefs and in the stories, we tell ourselves to make sense of the world.

By translating neural processes into computational language, we can say that out of the 10,000,000 to 12,000,000 bits our eyes perceive per second, we consciously process only 40 – just 0.003 to 0.004%. The likelihood that two people process the exact same 40 bits is extremely low.

When perceiving information, our brain immediately begins searching for patterns and structures to classify impressions. It follows specific processes, such as recognition, memory, associative thinking, and judgment. These processes, in turn, are largely influenced – often subconsciously – by personal interests and expectations. This can quickly lead us to perceive someone as brilliant, ignorant, foolish, or even sinister.

Such cognitive biases can also result in overestimating ourselves – something that happens to all of us from time to time. A U.S. study found that 95% of teachers rated their own teaching abilities as above average. Another study involving one million students revealed that 70% believed their performance was above average. Mathematically speaking, the average should be 50%.

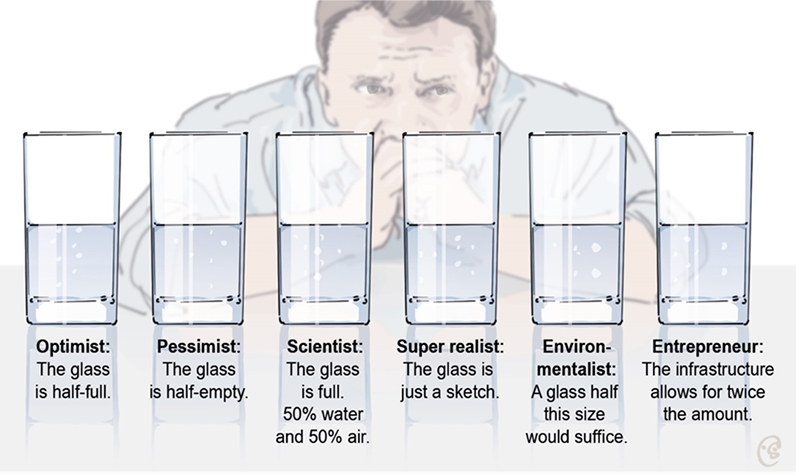

It is only when we activate our conscious and generally slow-thinking system – as Kahneman calls it – and begin to examine our own perspective that we open ourselves to other perceptions and opinions. The following graphics illustrate how experience, attitude, knowledge, needs, goals, and individual responsibility shape different perspectives, even when looking at the same thing.

The social bond between team members is the key to accepting diversity and otherness. People feel connected when they can build a positive relationship with others. The prerequisite for this is information—learning about personal backgrounds and stories helps us discover commonalities, creating emotional closeness.

Starting a positive conversation with someone who shares the same name, birthday, profession, or comes from the same country or city is easy for most people. Body language is another powerful tool for fostering emotional connection—a smile and a handshake can have a remarkable effect.

We are often asked whether the level of acceptance of diversity and otherness can be measured. It is probably possible, like most things, but we are not entirely sure. However, experience has shown us that true acceptance is evident when team members stop monitoring each other, when they begin listening more than they speak, and most importantly, when they let go of the need to always be right and become open to suggestions and new ideas.

Trust is one of the most powerful human emotions. When people trust one another, they are more likely to consider other opinions, accept various perspectives, and commit themselves to a common goal. To clarify, trust is not the only emotion strong enough to generate top performances, fear can achieve the same. However, using fear is generally not a good option due to the collateral damage it creates over time.

The three previous steps of our cycle are key to creating trust. The best way to successfully take these steps is by focusing on positive personality traits first, specifically looking at strengths. The road to success as a team always leads through individual and common strengths and never through discussing weaknesses. Addressing weaknesses almost always creates negative reactions and resistance.

Trust cannot be achieved by words alone; actions are important. Many companies write noble values on patient paper and post them on the wall for all to see. However, building trust requires a testing field where people can study and assess authentic behaviour. Role models are key. When every team member acts in a manner they would expect from others, it will inevitably lead to trust. Conversely, failing to match words with actions will destroy trust quickly and without fail.

These actions also involve subconscious processes, such as physical perceptions, a handshake, or perhaps a hug in appreciation. Trusting team members regarding their knowledge and professional experience is usually a conscious and rational attitude. The relationship aspect of trust is far more subconscious and harder to control. When everyone is pulling in the same direction, pursuing the same goals, and prioritising the team rather than themselves, trust will grow – subconsciously and slowly.

The first four steps of our cycle could also apply to a family or a group of friends. They can but must not be performance-linked. The fifth step, however, always is. Performance and success imply that there is a goal. Reaching this goal can only be done if there is a decision to do so. The more consciously and clearly this decision is made by every single team or organisation member, the more successful the project and team will be.

This is the moment to talk again about the notion of the cycle. While we present the decision as the fifth and last step of the cycle, it can also be – and sometimes should be – the first step. In reality, a starting decision for a project – and the team in charge of it – to be successful can actually move mountains, or, as the following example will show, unite countries. We believe this step is often underestimated or misunderstood. We often hear that this may be right for small projects but does not really work for very large projects and teams. Here is an example to the contrary.

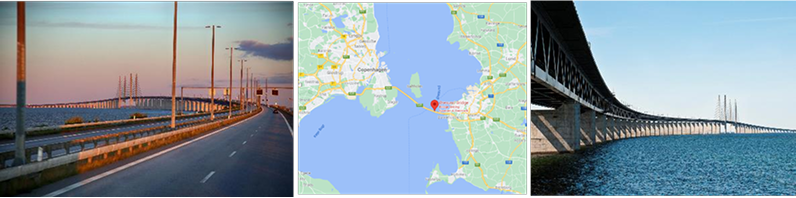

We all know how things usually go with large building construction projects. They tend to be finished years late and cost two or even three times the amount initially projected. It does not have to be this way, however. The Öresund Bridge connecting Malmö and Copenhagen spans over 8 km and includes a 4 km tunnel. It serves as a connecting piece between Sweden and Denmark. The gigantic project was not only inaugurated six months ahead of schedule, but it also cost significantly less than predicted.

When reading reports on the project carefully, one realises that the entire project was carried by the fundamental conviction that it would create added value. Not only for Europe and the countries and regions involved, but especially for the people who were most affected by the construction of the bridge. Accordingly, the concerns of those people, including critics and opponents, were taken seriously and considered in all sub-goals of the project. At the end of the process, everyone involved – from politicians to building contractors, from interest groups to local residents – felt they could back the common goal of creating this connecting bridge. So, they made a decision that simply did not include the scenario of the project failing.

Things could have gone wrong anyway, of course. But the project team never lost sight of the goal. They had committed – as a group – to react positively and flexibly to all changes, challenges, and opportunities that would come up along the way. They searched for sources of errors, looked at other opinions, compared perspectives, and remained flexible and open to adjustments.

We are certain that you can recall moments in your personal or professional life where failure was simply not an option—situations where everyone involved was so determined to succeed that challenges were overcome, and opportunities were seized without hesitation.

I have consciously written the above article in a We-form and not an I-form. The reason for this is quite simple. While I am indeed the individual who has written these lines, it would not be honest to claim that all the content has been created and developed by me alone. Our company PSYfiers was founded by four partners: Maike von Elverfeldt, Bernhard Mikoleit, Armin Neische, and me. A little later, Peter Kälin joined us, whose generous support has allowed us to survive the difficult time of the coronavirus pandemic. Without these four partners, the five-step cycle described above would look very different. Without these four partners, the five-step cycle described above would look very different. And, without them, our products such as the Visual Implicit Profiler (VIP), mission future, Mission Career, and Mission Team would not exist.

The same also applies to each of our team members. We actually practise what we preach ourselves. Each team member has been asked to discover their strengths when they start working for PSYfiers. We try to understand each other’s strengths and use them for the best of the team. We have implemented an error culture based on honesty and trust.

With hundreds of thousands of our products in use, we are confident that our approach delivers results for others as well. But we don’t just trust it – we know it works because we apply it ourselves every single day.

Curious about Mission Team and have a few questions?

Excited to dive deeper into what we offer?

Ready to transform your team with an incredible workshop?

We help people work better together 🏆

© 2025 Mission Team, Inc. All rights reserved.